Human beings are hardwired for survival, not for investing. The psychological traits that helped our ancestors survive in tribes and navigate danger now often hinder our ability to build long-term wealth. At Canopy, we believe managing our own behavioural biases is as fundamental to our investment process as our rigorous quality assessment or valuation discipline.

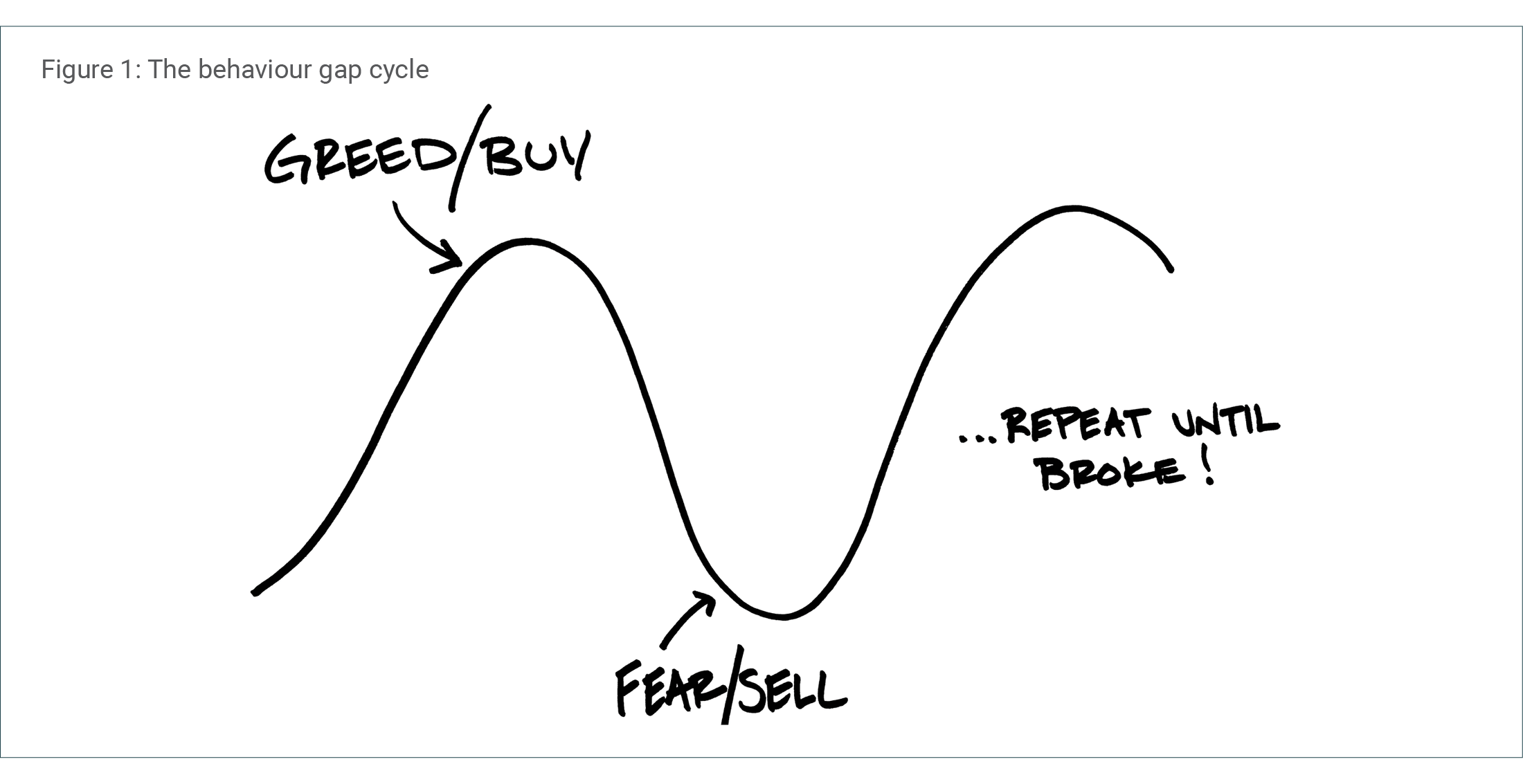

Buy high, sell low!

Investment returns and investor returns are not the same thing. Markets have historically rewarded patient capital, but most investors fail to capture these returns due to poor timing decisions, a phenomenon known as 'the behaviour gap'. It occurs because investors systematically buy after prices have already risen and sell after they have fallen, transforming market volatility from a potential opportunity into a source of loss. Understanding and defending against this dynamic is crucial for long-term wealth creation, as even small behavioural penalties compound dramatically over time.

Source: The Behaviour Gap, Carl Richards.

Source: The Behaviour Gap, Carl Richards.

This pattern has been consistently documented in studies of investor behaviour. As noted in Chapter 4, DALBAR's long-running analysis found that over the last three decades, the average US equity fund investor has underperformed the S&P 500 by 3-4% annually, primarily because of buying high and selling low during volatile periods (2022). Morningstar’s Mind the Gap study (2023) has reached similar conclusions, finding that the average dollar invested in funds earned a 10-year return to December 2022 that was 1.7% less annually than the average underlying fund.

Perhaps the most striking example comes from one of history's most successful fund managers. Peter Lynch managed the Magellan Fund at Fidelity Investments between 1977 and 1990, producing an annualized return of 29.2%. Yet it has been reported that the average investor in his fund made only 7% per annum (Jakab, 2016). Despite having access to exceptional investment performance, poor timing decisions cost investors the majority of their potential returns.

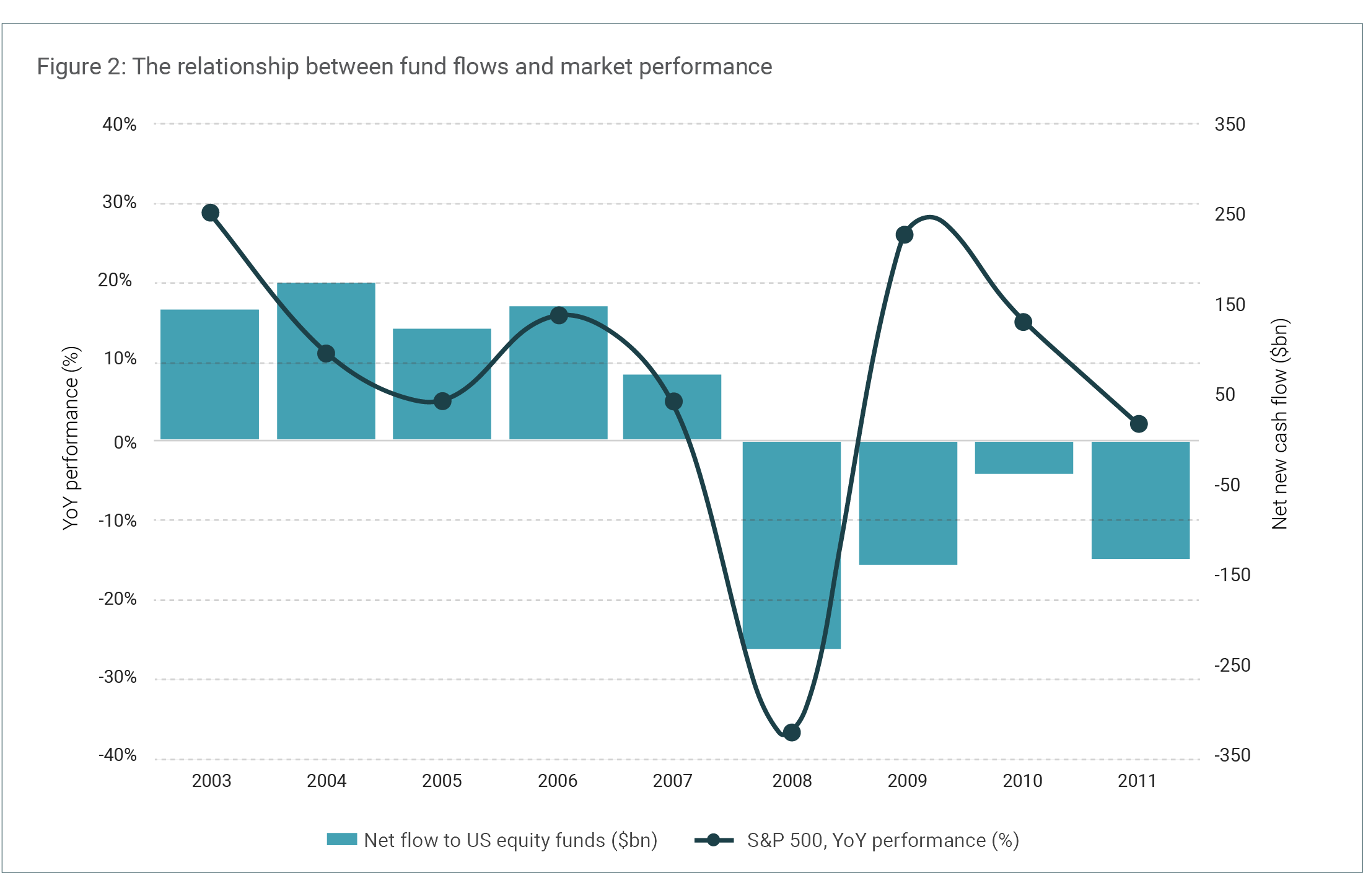

The behaviour gap tends to be most pronounced during periods of market exuberance or stress, as illustrated in Figure 2. In the lead-up to the GFC in 2007, equity fund inflows remained strong despite mounting economic risks. As equity markets declined through 2008, fund outflows accelerated dramatically, reaching their most negative levels during 2008-2009. As it turned out, this was actually a great buying opportunity. Crucially, outflows continued even after markets began recovering, with flows remaining negative through 2011 despite substantial market gains during this period. This timing pattern illustrates how investor behaviour often lags market turning points, leading to suboptimal entry and exit decisions.

Source: Investment Company Institute, Canopy Investors.

Source: Investment Company Institute, Canopy Investors.

When instincts backfire

To cope with the daily information overload, our minds rely on mental shortcuts called heuristics. While these shortcuts serve us well in many aspects of life, they can also work against us. Several behavioural biases are particularly problematic for investing:

- Confirmation bias causes us to seek information that supports our existing beliefs while ignoring contradictory evidence. An investor convinced of a company's potential might focus on management's optimistic guidance while dismissing customer complaints, executive departures, or deteriorating financial metrics.

- Overconfidence tricks us into believing we can predict outcomes with greater certainty than we actually can. This might manifest as an investor who has enjoyed success with a few stock picks becoming convinced they can time market cycles, leading them to make increasingly concentrated bets or using leverage.

- Loss aversion makes losses feel more painful than equivalent gains feel pleasurable. This asymmetry leads to seemingly irrational behaviour: holding losing positions for too long (hoping to ‘break even’) while selling winners too quickly (to ‘lock in gains’).

- Hindsight bias convinces us we ‘knew it all along’ after events unfold, preventing us from learning from our mistakes. An investor might remember being ‘cautious’ about a failed investment when their notes actually show they were highly confident at the time of purchase, preventing honest post-mortems that could improve future decision-making.

- Groupthink emerges when teams prioritise harmony over critical thinking. Investment committees might reach consensus not because the analysis is sound, but because challenging the prevailing view feels uncomfortable.

- Recency bias leads us to overweight recent events when making decisions. Investors often chase last year's best-performing asset class assuming recent trends will continue indefinitely. This backwards-looking approach systematically buys high and sells low, as yesterday's winners often become tomorrow's laggards.

- Herding makes us feel comfortable following the crowd, even when the crowd is heading toward a cliff. The Dutch tulip mania, the South Sea Bubble, and the housing bubble all shared a common thread: rational people making irrational decisions because ‘everyone else was doing it’.

Source: Tom Fishburne.

Source: Tom Fishburne.

These biases often work in combination, amplifying their individual effects. Recency bias might lead an investor to chase last year's hot sector, while confirmation bias ensures they only read bullish research, and overconfidence convinces them to make an oversized bet. When a reversal eventually comes, loss aversion prevents them from cutting losses quickly, and hindsight bias ensures they learn nothing from the experience.

Our approach

The late Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman reached a somewhat disheartening conclusion at the end of his influential book ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’: there is little we can do as individuals to prevent behavioural biases from influencing our decisions. He considered that objectivity is easier when evaluating others’ decisions than our own; “it is much easier to identify a minefield when you observe others wandering into it than when you are about to do so.”

At Canopy, we have adopted team and rules-based processes to minimise individual biases, with our flat structure serving as the foundation:

- Institutionalized dissent: We have deliberately built structured debate into our process, recognising that it is often easier to spot flaws in someone else’s reasoning than in our own. Every position in the Fund has a ‘secondary analyst’ whose primary task is to act as devil's advocate to the primary analyst's view. This structure reduces the prospect of groupthink and confirmation bias by forcing alternative perspectives into every investment discussion.

- Independent conviction ratings: Each team member maintains independent views on stocks, and these views directly impact portfolio construction. Ratings and comments are recorded and reviewed when performing post-mortems on positions, increasing accountability among all team members, reducing hindsight bias, and accelerating learning from both successes and failures.

- Pre-mortem analysis: Before taking positions, we routinely perform pre-mortems, where we imagine our thesis is incorrect a couple of years into the future and consider what might have gone wrong. This exercise reduces groupthink, confirmation bias, and overconfidence by forcing us to actively consider how our thesis might be wrong.

- Multiple valuation approaches: We use several valuation methodologies to avoid the pitfalls of relying on simple multiples or heuristics alone. Additionally, our valuations are expressed as ranges rather than point estimates, helping to reduce overconfidence, and acknowledging the inherent uncertainty in any valuation exercise.

- Disciplined selling framework: To combat loss aversion, we maintain strict sell discipline. We are particularly vigilant about selling stocks where there has been material ‘thesis creep’ – gradual changes to our original investment rationale that often signal we are rationalising poor performance. In our experience, these situations frequently become value traps. For high-quality companies, we more gradually reduce positions when valuation becomes the primary concern.

- Variant perception: When investing in any stock, we work to identify our source of edge and how our view differs from the market consensus. Since markets are typically efficient, the best opportunities arise when we can disagree with the consensus while maintaining strong conviction in our analysis.

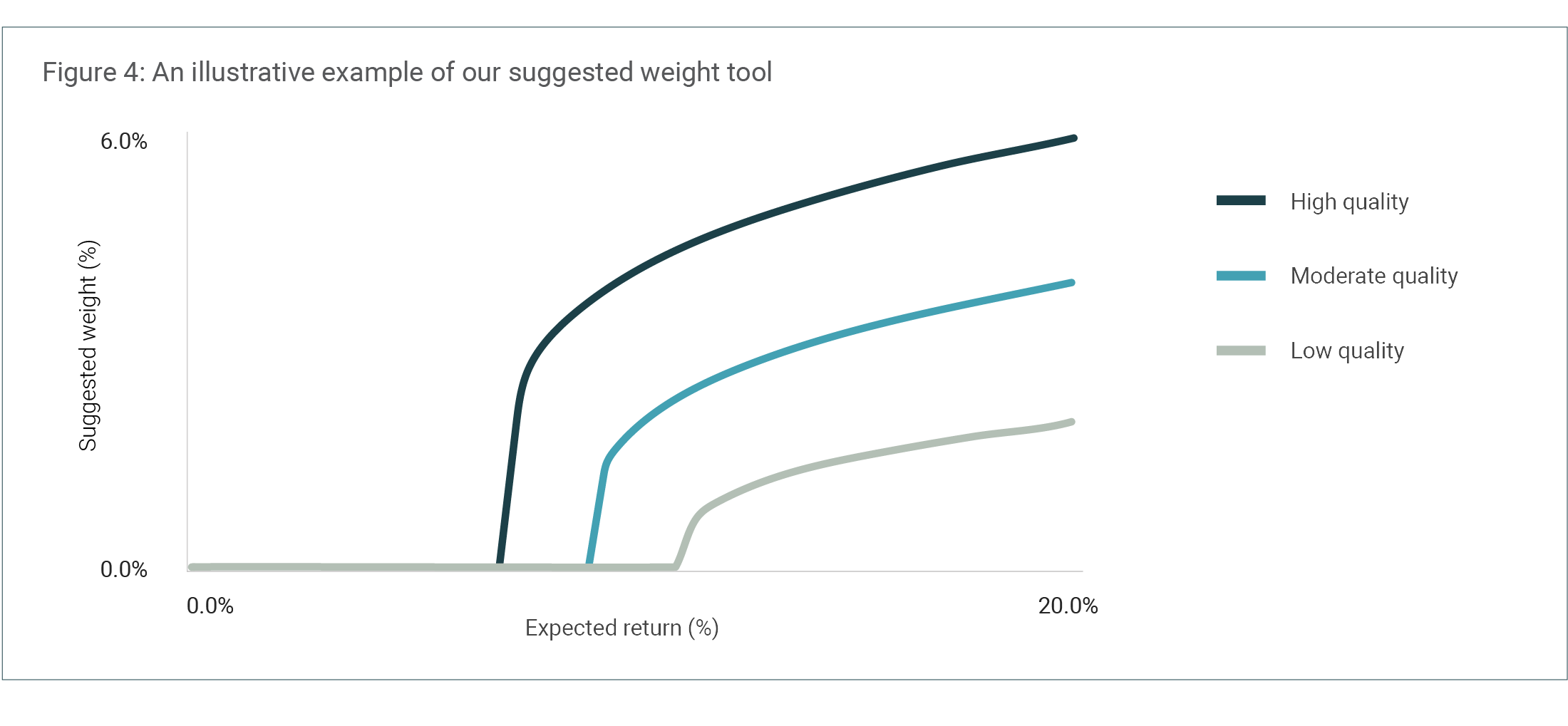

- Systematic position sizing: We use a systematic tool that translates our quality and valuation assessments into suggested portfolio weights. As illustrated in Figure 4, higher-quality companies are allocated a substantially larger position size for any given expected return.1 As these weights change daily with share prices (and less frequently with our fundamental assessments), we are prompted to dispassionately evaluate position sizes, helping to reduce the influence of recency bias and emotion.

- Decision quality over outcomes: We seek to evaluate the quality of our decisions rather than judging success solely according to outcome. This distinction helps us learn from both wins and losses by focusing on whether our analysis was rigorous and our reasoning sound, rather than results that may reflect luck or short-term market movements.

Source: Canopy Investors.

Source: Canopy Investors.

While no process can eliminate mistakes entirely, ours is designed to reduce the risk of material missteps and support more disciplined position sizing. We accept that we will make mistakes, but by identifying potential pitfalls before committing capital – not after – we improve our chances of avoiding them. The same behavioural traits that once helped humans survive can undermine investment decisions. Our process has been designed to help our portfolio succeed in spite of them.

Bibliography

DALBAR, Inc. (2024). Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior 2024.

Investment Company Institute (2012). 2012 Investment Company Fact Book.

Jakab, S. (2016). Heads I Win, Tails I Win: Why Smart Investors Fail and How to Tilt the Odds in Your Favor. Crown Business.

Kahneman, D (2011). Thinking Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Morningstar (2023). Mind the Gap: A Report on Investor Returns in the U.S.

[1] Importantly, the 'low quality' rating is relative to our high-quality investment universe - these are still fundamentally strong businesses that meet our quality criteria, just at the lower end of our spectrum.

The content contained in this article represents the opinions of the authors. The authors may hold either long or short positions in securities of various companies discussed in the article. The commentary in this article in no way constitutes a solicitation of business or investment advice. It is intended solely as an avenue for the authors to express their personal views on investing and for the entertainment of the reader.