Warren Buffett has previously observed that for information to be useful in investing, it must be both important and knowable. While macroeconomic outcomes are undeniably important, evidence suggests they cannot be predicted with useful accuracy.

The forecasting fallacy

The track record of professional macro forecasting is remarkably poor. Prakash Loungani's 2001 study analysed consensus GDP growth forecasts from private sector economists across sixty-three countries, examining sixty recessions from 1989 to 1998. His analysis showed that only two of the sixty recessions were predicted a year in advance, two-thirds remained undetected by April of the recession year, and in about a quarter of cases forecasters were still predicting positive growth in October of the recession year. As Loungani concluded, "the record of failure to predict recessions is virtually unblemished."

Major institutions perform no better despite employing teams of PhD economists and having privileged access to non-public information. Andrew Brigden of Fathom Consulting examined International Monetary Fund (IMF) predictions across 194 countries, analysing 469 economic downturns from 1988 to 2018. The IMF successfully predicted only four recessions a year in advance - a success rate of just 0.85% - with all successful predictions involving smaller developing economies rather than major markets.

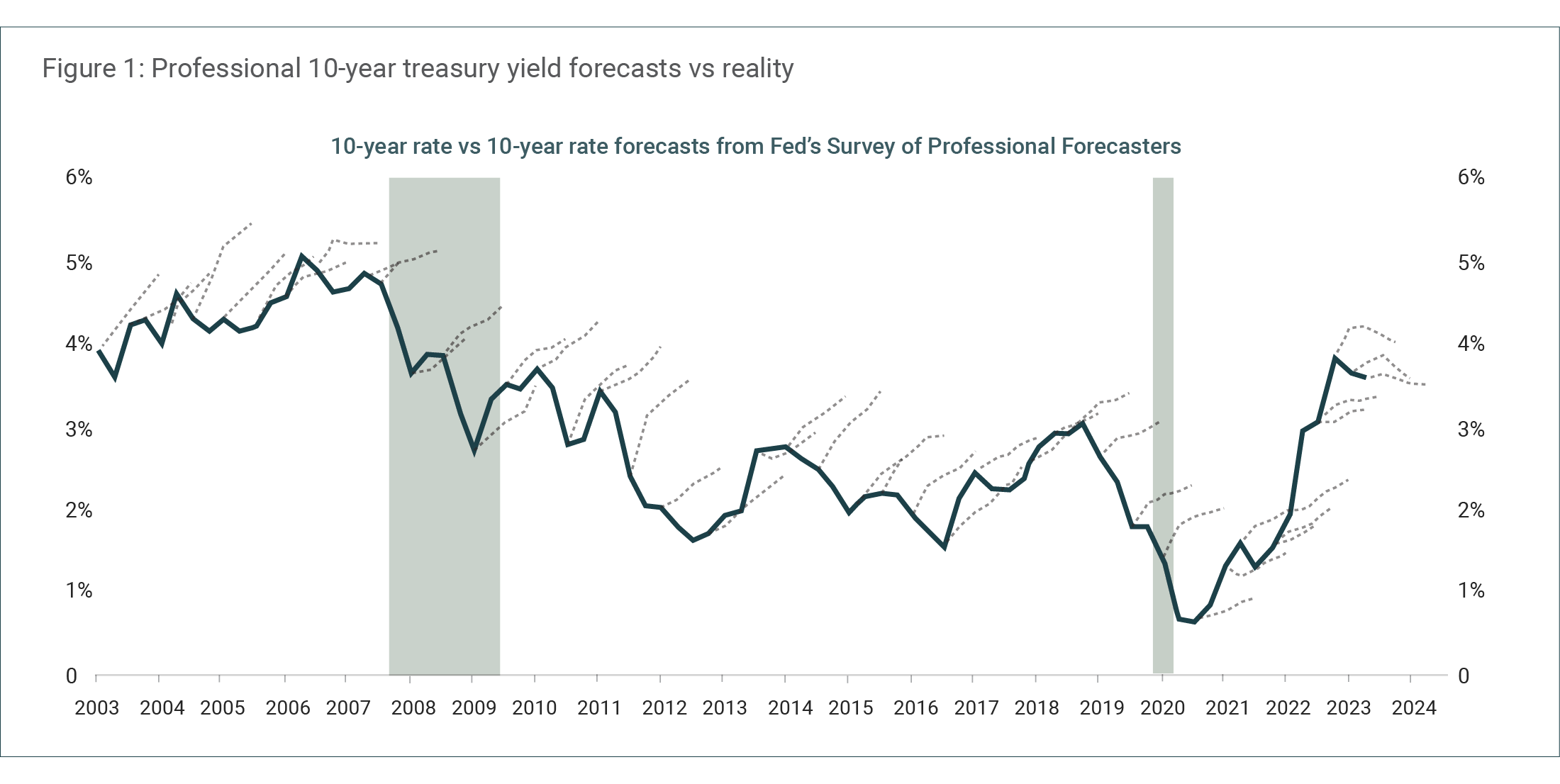

This pattern extends beyond recessions to other key macro variables. Figure 1 below shows two decades of professional interest rate forecasts consistently overestimating future yields and missing every major decline.

Source: Bloomberg, Philadelphia Fed Survey of Professional Forecasters, Apollo Chief Economist.

Source: Bloomberg, Philadelphia Fed Survey of Professional Forecasters, Apollo Chief Economist.

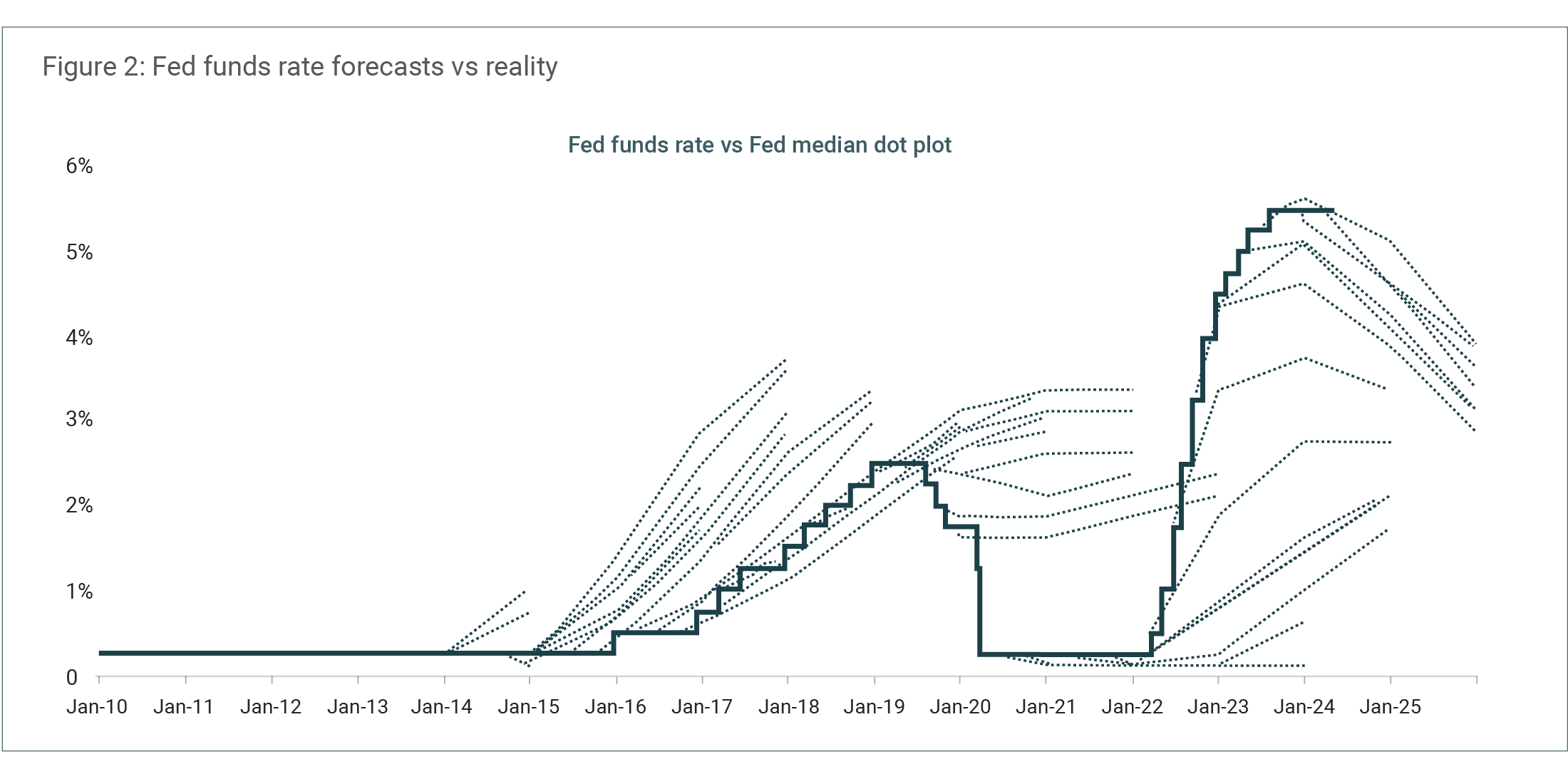

Tellingly, the Federal Reserve struggles to predict even its own policy decisions. Figure 2 below highlights how Fed officials' projections of the funds rate (a metric they directly control) consistently miss the mark by wide margins.

Source: FOMC, Bloomberg, Apollo Chief Economist.

Source: FOMC, Bloomberg, Apollo Chief Economist.

The double prediction problem

Imagine that you could predict every recession, every inflation spike, and every policy change. Would you be guaranteed investment success? The surprising answer is no. As Howard Marks explains, "Even if you somehow manage to get an economic forecast correct, that's only half the battle. You still need to anticipate how that economic activity will translate into a market outcome. This requires an entirely different forecast, also involving innumerable variables, many of which pertain to psychology and thus are practically unknowable."

We see this challenge in action when identical economic news can drive markets in unpredictable, sometimes opposing directions depending on prevailing sentiment, prior expectations, and what's already priced in. Lower inflation could spark a rally (rate cuts ahead!) or trigger selling (economic weakness!). The recent inflation cycle illustrates this perfectly. Economists consistently underestimated how aggressively the Fed would raise rates to combat inflation, forecasting a peak Fed funds rate in 2022 of around 3.5% when it actually reached 5.25-5.50%. Yet even perfect rate forecasting wouldn't have helped predict the subsequent market behaviour. Basic finance theory suggests higher rates should pressure valuations, but the S&P 500 has hit repeated record highs since then, powered most recently by optimism around artificial intelligence. Perfect economic forecasting, in other words, is only half the challenge.

Our approach

In our view, attempting to invest based on macro predictions is at best a distraction, and at worst deleterious to returns. But that doesn't mean we ignore the macro environment. At Canopy, we've sought to develop an approach that acknowledges macro uncertainty while still positioning our portfolio thoughtfully:

- Focus on ranges, not point estimates: While it's impossible to avoid making implicit macro assumptions when investing, we have sought to minimise our reliance on any single economic scenario. Instead, we consider a range of potential outcomes and position accordingly. This reduces the requirement to predict the next inflation print or divine currency movements – rather, we simply need to avoid positioning the portfolio to succeed in only one economic environment.

- Diversify: We invest in high-quality companies that can adapt and thrive across different economic conditions. Our portfolio includes businesses that would benefit from economic acceleration alongside others that offer defensive characteristics during downturns. We also seek exposure to different geographies and industries to avoid concentrated exposure to any single economic cycle.

- Remain fully invested: We don't believe we can time markets, and so remain fully invested. Over time, we expect high-quality, reasonably-priced companies to increase in value as they adapt to economic circumstances and grow their businesses. Our broad investment universe and ever-changing markets should ensure we can consistently find attractive opportunities without needing to predict the best time to deploy capital.

This approach reflects our belief that successful long-term investing focuses on what we can control - identifying quality businesses at attractive prices - rather than attempting to predict the unknowable.

Bibliography

Brigden, A. (2019). The economist who cried wolf? Fathom Consulting.

Loungani, P. (2001). How Accurate are Private Sector Forecasts? Cross-country Evidence from Consensus Forecasts of Output Growth. International Journal of Forecasting, 17(3), 419-432.

Lynch, P., & Rothchild, J. (1996). Learn to Earn: A Beginner's Guide to the Basics of Investing and Business. Simon & Schuster.

Marks, H. (2022). The Illusion of Knowledge [Memo]. Oaktree Capital Management.

The content contained in this article represents the opinions of the authors. The authors may hold either long or short positions in securities of various companies discussed in the article. The commentary in this article in no way constitutes a solicitation of business or investment advice. It is intended solely as an avenue for the authors to express their personal views on investing and for the entertainment of the reader.